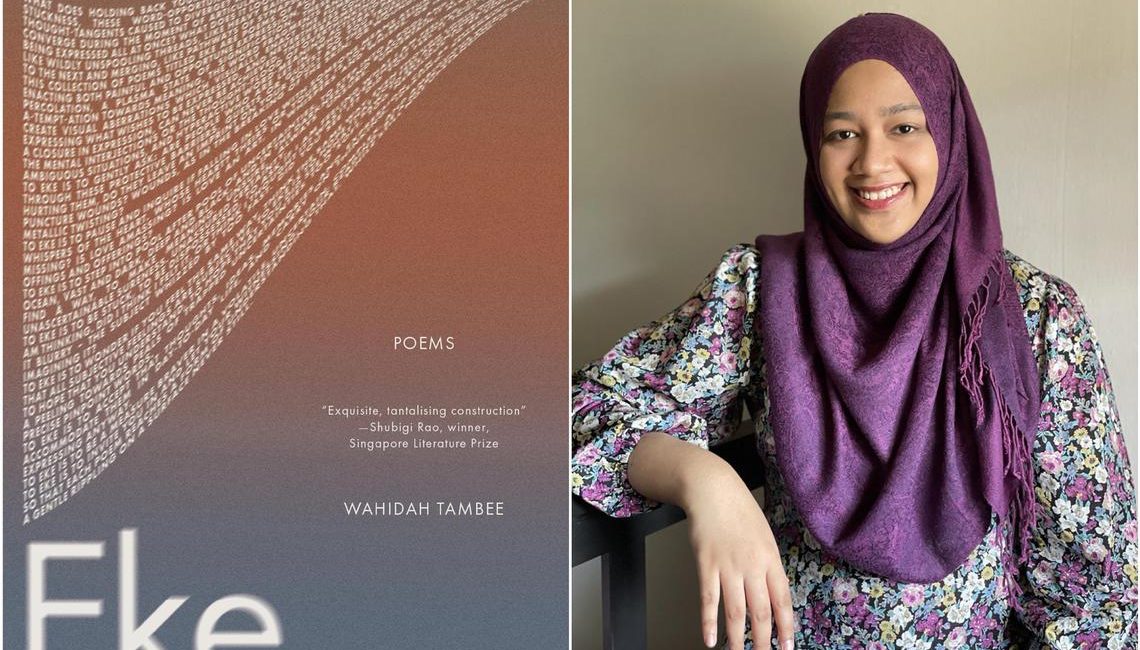

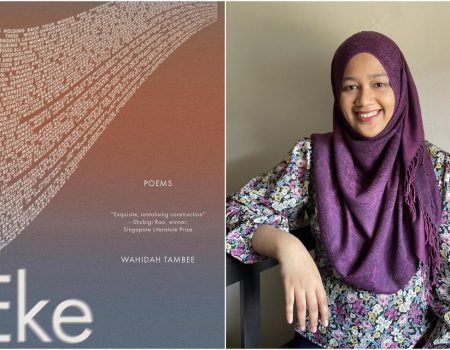

By Wahidah Tambee

Poetry/Gaudy Boy/Paperback/106 pages/$19

Each poem is an island – no, an islet – in Singaporean poet Wahidah Tambee’s typographically dense Eke. Words, often just letters, cluster around a single patch of each page, such that thumbing through the collection feels like one is rifling through a folio of 40 old maps to a lost archipelago in a white sea.

An excerpt from poet Wahidah Tambee’s typographically dense Eke (2025).

PHOTO: GAUDY BOY

Where then do these 40 concrete poems in this mesmerising debut collection point the reader to? The poems’ inability to speak in the genre’s lingua franca – continents of stanzas, the latitude of the line – make visible the difficulty in articulating some themes that float throughout the book: grief, terror and erasure, among others.

But not all the poems deal with such aphasia turned into visual stutters. A poem like “sunrise” can read like a simple visual translation of the nature poem – austere in its execution, a few ambiguous brushstrokes conjuring the entire landscape.

Each poem makes do with its scarce resources – alphabetically (10 letters in the opening poem) and typographically (sized like a thumb). With overlapping leading (that is, the space between lines of type), they invite multiple ways of reading – does this one say “letter / let us tell her / she left us” or “letters / terse / tell us she let us”?

After all, the art of being an islet is the art of ekeing out an existence from not much. An islet’s existence is improbable and ephemeral – two Indonesian islands vanished in 2020 and a chain of West African islands is on the brink of disappearing.

These poems assert themselves on the page even as they appear like they are sinking or resemble eraser dust on the page (see the poem “erasuredust”).

Like islets, Wahidah’s poems are places for the visitor to project his or her fantasies – they do not take their sovereignty for granted. In her poems, the word “dismiss” is contiguous with “missile”, a stumble away from “dismally” (which contains the word “ally”) and “mull”.

Thus, the poems in Eke are not so much texts as they are musical scores – inviting the reader to interpret and improvise. The poet’s own performances of the poems at multiple readings this reviewer has attended are but one entry point into the poems, but they are by no means authoritative versions of these slippery creatures.

In its stuttering and attempt to find a language for the inexpressible, Eke is reminiscent of prominent poetic antecedents. For example, Canadian poet M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! (2008) erases legal documents from a 1781 massacre of around 150 enslaved Africans to stir up a voice from a voiceless people. The American modernist Gertrude Stein’s playful and cubist deconstruction of syntax in poetry also countered the representational arts.

In the book’s afterword, Wahidah writes that her fragments “recreate the mental interjections or the thought-flood of overthinking caused by polysemantic words, ambiguous situations, and hyperactive word-meaning activations”.

But the poems in Eke are not quite backed by the conceptual heft and rigour that lend weight to the formal experimentation with language’s deconstruction and erasure.

Still, these are poems attuned to the minutiae of language – its sounds, constituent letters and polysemy. Each word, in Wahidah’s hand, contains an excess of a dozen meanings and opens up pathways to a word’s potential beyond etymology. Eke is a distinct debut and a fresh voice in Singapore poetry.

Rating: ★★★★☆

The International Left-Hand Calligraphy Association by Tse Hao Guang

(Tinfish Press, 2023, $35.42). With its poems resembling calligraphic ink diffused on the page, the Singaporean poet’s second full-length collection is in natural conversation with the visually adventurous Eke.

No Comment! Be the first one.