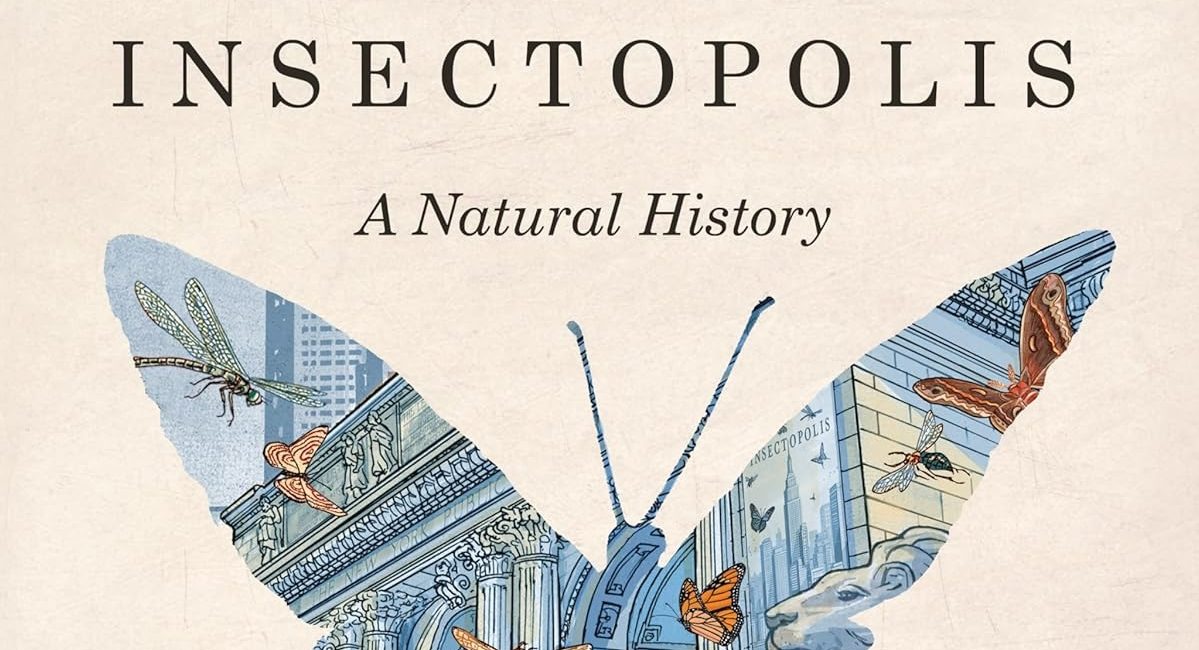

Peter Kuper’s book-length comic, Insectopolis: A Natural History, begins with an entomologist and her brother walking to the New York Public Library to see an exhibition on insects entitled “Insectopolis.” The sister rhapsodizes about the insects living hundreds of millions of years ago and how they persisted through the millennia when other creatures perished. The pair are just outside the Library when they receive a text alert telling them to go home immediately. A week later, we see an overturned car on an empty street, and then “Much (much) later,” a swarm of insects of all sorts is making its way toward the Library. Evidently, humans have not survived their own Great Extinction event, and insects can now read and speak.

The rest of the book allows insects to tell their stories, with the help of the display cases in the exhibit, a sentient library computer, talking statues, and the ghosts of great naturalists and entomologists. Kuper held a fellowship at the NYPL during the pandemic, so he was able to wander through the building all alone, and his fellowship led to an exhibition of his work, so there is a strong autobiographical component to the book. However, even if it was inspired by real life events, imagination is clearly the guiding force in this inviting dip into the insect world.

One of the funniest bits is the life and times of the dung beetle, which begins with a beetle of another species telling a joke: “Dung beetle walks into and bar and asks the bartender, ‘Is this stool taken?’” In fact, the dung beetle maintains, his species is not a punchline but has been worshipped as a god and is the first animal on earth to navigate by the stars. The dung beetle is give ample pages to spin his yarn, and we also learn about hover flies, which mimic bees; the role (often negative) played by mosquitoes throughout human history; how ants became “a projection of the destructive force humans had unleashed” during the Atomic Age; the reason silk moths are blind (“Humans bred us strictly for our silk. They didn’t need us to fly or even see”); the ravenous nature of dragonflies; the amorous devotion of termites (the king remains by the queen’s side for his entire four-year life span); and the way that Eastern Monarchs navigate, over four generations, from the Rocky Mountains to central Mexico.

There are a lot of fascinating facts, and Kuper’s decision to involve humans in the storytelling makes those stories more interesting. I was especially moved by the appearance of Margaret Collins and Rachel Carson. Their ghosts first materialize as little girls, and we learn that Collins was a brilliant entomologist whose work was stymied for most of her life by the fact that she was an African American woman. Carson, of course, is the author of Silent Spring, the expose of DDT’s deleterious effects on the environment. She died of cancer in 1969, at the age of 54. As they rehearse their life stories, they grow into adult women, but as those stories come to their conclusions, they revert to children and disappear out the front door of the museum.

Insectopolis is a book for adults, not children, but I could certainly envision a bright pre-teen enjoying most of the panels. And what panels they are! They range from two-page spreads with little or no text to smaller, densely illustrated frames rich with imagery and facts. The variety and pacing are superb — not surprising, considering how accomplished Kuper is — and this is one of those books that invites lingering while never losing its momentum. If nothing else, it’s bound to make a reader appreciate the creepy-crawlies we too often ignore or thoughtlessly attempt to destroy.

This review originally appeared in the California Review of Books.

No Comment! Be the first one.